Eastern Black Walnut (Juglans nigra L.) : Physical Characteristics and Natural History

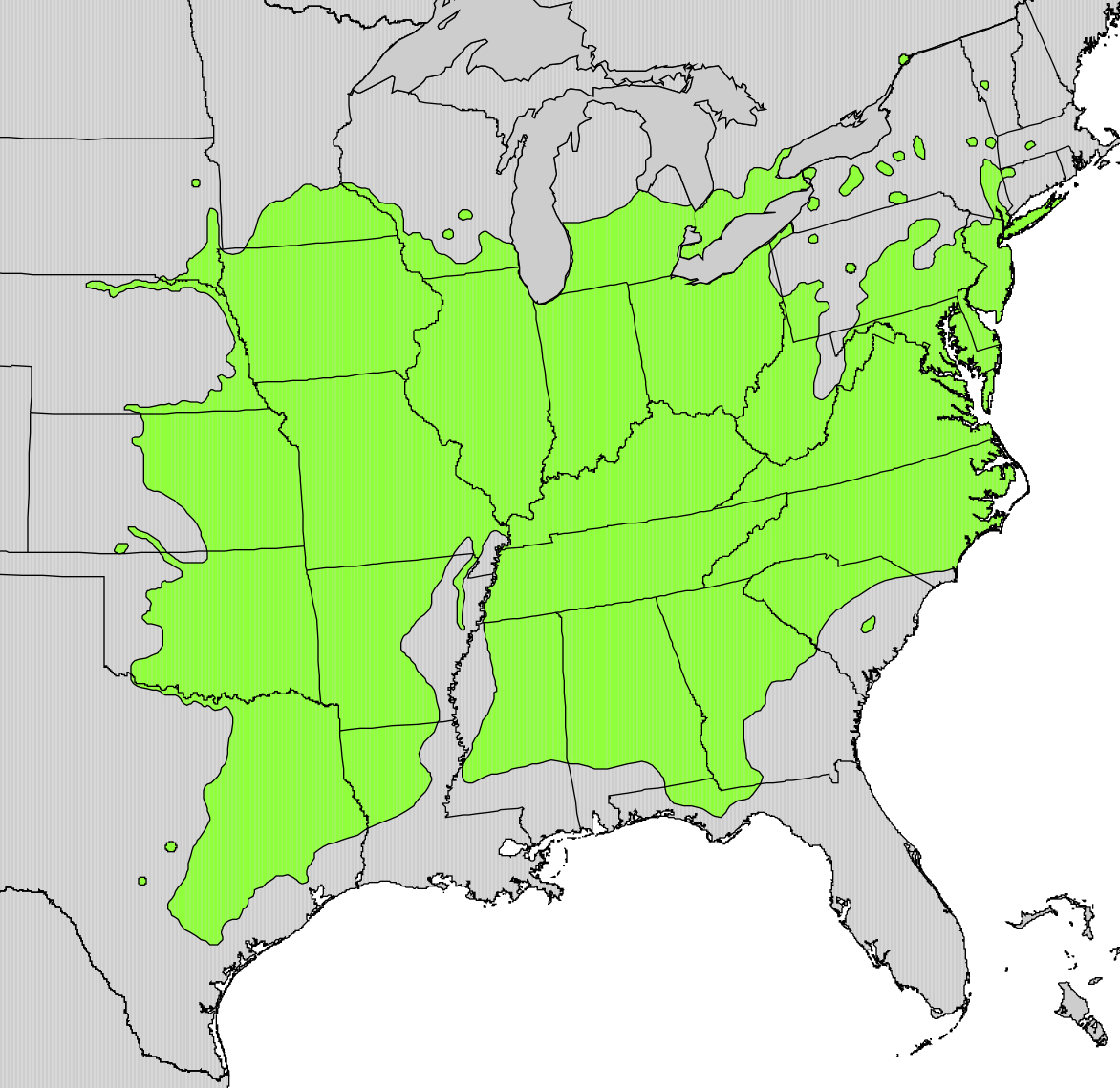

Range and distribution map of Juglans nigra L. (Digital representation by Elbert L. Little, Jr., U.S. Geological Survey, 1999).

There are over 20 different species of walnut, distributed throughout the world, from Persia (English Walnut, J. Regia), all the way to California (California Black Walnut, Juglans californica). Yet, the Eastern Black Walnut, the Juglans nigra L., is endemic to the eastern half of the U.S. in temperate deciduous forests. The Black Walnut tree is often found near other hardwoods, rather than in pure-stands.

While it can survive in the northern latitudes, the black walnut prefers the central and southern regions of the U.S. rather than in the northeast since northern soils tend to be more acidic and, of course, colder. That is one of the reasons why Vermont is home to few Black Walnuts compared with other states. In fact, almost all of the New England population of Black Walnut was planted. That being said, it is not surprising that UVM has only two black walnut trees on the entire campus in fairly inconspicuous locations. According to the UVM tree inventory, there are only two Black Walnut trees on campus, both of which are mature. One is along South Prospect Street near the ALANA House and the other is near the Englesby House where UVM president Tom Sullivan currently lives.

The black walnut has a green, fleshy exterior when it first falls of the tree before it darkens (Bruce Marlin, 2005).

Black Walnut trees prefer full sunlight, and when planted, seeds flourish in deep, nutrient and mineral rich soil full of organic matter that is well drained. The Black Walnut can rise to 150 feet tall, branches outstretched widely, forming a large canopy overhead. Its deeply grooved bark, brown-grayish in color, creates a diamond pattern. The leaves are complex and alternate with a range of nine to 23 leaflets per leaf, which usually span between 30 to 60 centimeters long. The largest leaflets are situated in the center of the leaf and are seven to 10 centimeters long and two to three centimeters wide. The leaves flower in May to late June. The male flowers are catkins eight to 10 centimeters long, while the female flowers mature into the fruits in bunches of two to five come fall. The male and female flowers are present on the tree at different times, an evolutionary and adaptive measure to avoid inbreeding, and as a result, two separate trees are needed to create a fertilized seed.

The spherical fruits are around four to six centimeters in diameter and are a fleshy yellow-green color. Over time, the fleshy part of the fruit (the husk) changes from green to a rich black, staining everything it touches. The husk is rich with tannins, and inside, a rock-hard, tough shell, otherwise known as the hull, protects the nutmeat, as it is thick and grooved, similar to the tree’s bark. The nuts are fully developed and fall off the tree come mid September. Squirrels can often be found munching on black walnuts, while caterpillars and Luna moths eat the leaves.

Without its leaves, the black walnut tree stands tall in this deciduous forest ("Black Walnut" by Albert Herring, 2012).

The Black Walnut has biological capabilities help it survive such as its unique compound juglone. Juglone is naturally present in the leaves, roots, bark, and fruit of the tree in varying concentrations. The Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) is alleopathic, meaning that it produced biochemicals, juglone in this case, to impede the survival and growth of other organisms in its proximity. As parts of the tree break down into the soil, juglone is present mostly in the roots stunting and even killing other plants that try to grow. This area of toxicity stretches for approximately 50 to 60 feet from the trunk, expanding as the roots grow out. This survival mechanism ensures that the Black Walnut has less competition for nutrients and water under its canopy. The chemical Juglone is sometimes used as an herbicide and a dye, as well as means for coloring certain foods and cosmetics.