Becoming Frances : Aunt Nancy

Frances moved to Newbury when she was two years old and over the years of her childhood she became close to members of her Johnson family and her “cousins,” a term that she described as covering “all the descendants of General Jacob Bayley and Colonel Thomas Johnson” as well as the Hales, the Darlings, the Cobbs, and other families. [1] Frances especially like the older women of Newbury. They were not “highly educated in a scholastic sense, or widely traveled or even moderately wealthy,” she wrote, but they “determined the pattern of life” in the town, were “industrious and frugal and, withal, hospitable, kindly, enlightened and, in several cases, extremely devout.” From them, Frances learned “that a woman does not need any of the attributes or advantages, which I have admitted its members lacked, to be an active force and a guiding star; she may achieve both ends through simple goodness and homely wisdom coupled with courage and contentment and illuminated by faith.” [2]

The women of Newbury were collectors and tellers of stories and one of the best storytellers was, according to Keyes, “an old lady whom we all called Aunt Nancy.” She told stories about “a lovely young queen who rode through the streets of a great city in a golden coach and about an empress who lived in a palace of another great city and yawned behind her painted fan when she became bored during the long ceremonies at which she was called upon to preside.” What Keyes only learned later was that the stories she thought were an old lady’s fairy tales were actually reminiscences of a woman’s youthful journey to Europe. [3]

Aunt Nancy, whose full name was Anna Nancy Cumming Johnson, born in 1818, was the daughter of David Johnson. During her convalescence after having her right foot amputated, Johnson wrote Letters from a Sick Room, an inspirational book that was anonymously published by the Massachusetts Sabbath School Society. [4] Two other books followed, written while she taught school. In 1847, during a trip to a water cure resort in Brattleboro, Vermont, Johnson met the educational reformer Catherine Beecher and the two women joined forces to establish women’s colleges on the western frontier. [5]

After returning east, Johnson settled in Saratoga Springs, New York, to take the waters and write about Saratoga’s social life for local newspapers. Her articles came to the attention of Henry J. Raymond (UVM Class of 1840), who co-founded the New York Times in 1851 and was its editor from then until his death in 1869. Raymond helped Johnson get published a collection of her stories and an ethnography of the Iroquois. He also hired her as a foreign correspondent for the Times and she published her travel articles under the initials A. J. and the pen name Minnie Myrtle.

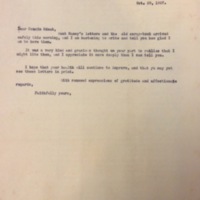

In 1902, a history of Newbury, Vermont was published and it included a long recollection of Nancy Johnson by Mrs. A. G. Johnson. According to Mrs. Johnson, Nancy Johnson’s “mind first began to break down” during her European travels because she was “too anxious” a woman “to be independent” despite having “an immense amount of energy and pride.” Her intellect was “something wonderful. But it was a great mistake for her to be left so alone. She needed (like all geniuses) a kind, honest, practical friend to stand by her, and take care of her.” [6]

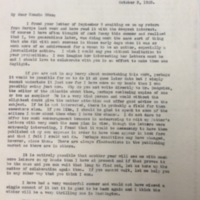

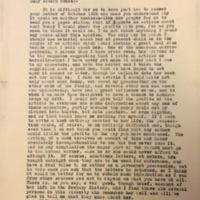

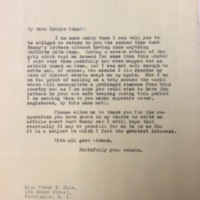

In the early 1920s, Edna Hale, a Johnson cousin, decided it was time to tell a different story about Aunt Nancy and she asked Keyes, who had by then published articles about other residents of Newbury, to participate in the project. Finally, in 1939, Keyes composed an article about Aunt Nancy for the National Historical Magazine, which she was then editing for the Daughters of the American Revolution. She told Aunt Nancy’s story again in Roses in December. In Keyes’s recounting of Nancy Johnson’s life, Aunt Nancy’s story is a tale of fortitude, where success pivots not on fate but intention. Nancy Johnson was, according to Keyes, an “obscure cripple” who “carved out a career for herself that would be remarkable even now, and which in that day and age was phenomenal.” In this rendition, Aunt Nancy is a career woman “buoyantly” producing writings and she serves as a lesson to women about how “achievement is not dependent on health or success or opportunity.” In the conclusion to her article, Keyes concentrates on Aunt Nancy’s abilities as a storyteller to explain how her aunt’s stories inspired her own career as a writer. The stories Aunt Nancy told the young people of Newbury “spurred these children on, in time, to try their own fortunes in a waiting world – among them a grandniece, who was, in time, to fight her own way up from invalidism, to try and build a profession on dreams and determination, and to go forth, as the representative of a great magazine, to visit courts and to sail the seven seas.” [7]

Keyes realized, she told her cousin Edna Hale, “that I, two generations later, was doing much the same sort of thing that she did with such success in those early days when it was so much more of an achievement for a woman to be an author, especially a journalistic author.”

Notes:

1) Roses, 57. ↵

2) Roses, 147-148. ↵

3) Roses, 64. ↵

4) Anonymous [Nancy Johnson], Letters from a Sick Room (Boston: Massachusetts Sabbath School Society, 1845. ↵

5) Kathryn Kish Sklar, Catherine Beecher: A Study in American Domesticity (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973. ↵

6) Frederic P. Wells, History of Newbury, Vermont, From the Discovery of Coos County to Present Time (St. Johnsbury, VT: Caledonian Co., 1902), 595. ↵

7) FPK, “My Aunt Nancy: A ‘Lady Journalist’ of the ‘Timid Fifties,’” National Historical Magazine, August 1939, 14-26. ↵

Related Documents