Becoming Frances : Family

Louise Fuller Johnson was born in 1848. Her father, Edward Carlton Johnson, born in Newbury, Vermont in 1816, was the son of David Johnson, who was the son of Thomas Johnson, one of Newbury’s founders. Edward studied at Dartmouth and read law in Montpelier before moving to New York City, where he married Delia Marie Smith, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Delia “was a New Yorker, born and bred,” Keyes later wrote about her grandmother, “with the drawing-room of a corner house on Madison Avenue – at that time the center of fashion – as her social background.” [1]

Louise moved from her parents’ luxurious home in 1868 when she married her first husband, James Underhill, a New York lawyer. They had a son, James, Jr., born in 1871. In 1878, Louise’s father and husband died and while Delia dealt with her loss by traveling in Europe Louise stayed closer to home. Within two years she had met and married John Henry Wheeler, a tutor in Classics at Harvard. Their daughter, Frances Parkinson Keyes, was born on July 21, 1885.

John Henry Wheeler’s roots were also in Vermont. His father, Melancthon Gilbert Wheeler, was born in 1802 in Charlotte, Vermont, studied at Union College and Princeton Theological Seminary, and, after becoming an ordained Congregational minister, held different clerical positions in New England, eventually settling at a parsonage in North Woburn, Massachusetts. John Henry, the ninth of Melancthon’s twelve children and the second child of his second wife, Frances Cochrane Parkinson Wheeler, was born in 1851.

Frances Cochrane Parkinson Wheeler was a role model for her namesake granddaughter Frances Parkinson Keyes. Growing up one of eight children in a rural New Hampshire household, Grandmother Wheeler gleaned all she could from the local public schools and at age fourteen began teaching at several academies in the area. Seeking more schooling after she graduated from Nashua Academy, Grandmother Wheeler matriculated at Mount Holyoke College in the mid-1840s. Keyes later described her grandmother’s achievement as “the longed-for goal of almost every intellectually ambitious young woman in New England” and was clearly proud that her namesake grandmother had “attained an education which few women of her generation were able to boast of.” [2]

John Henry Wheeler, a graduate of Harvard (B.A., 1871; A.M., 1875), received his PhD in Bonn, Germany in 1879. After their marriage in 1880, John Henry and Louise moved from Cambridge to Brunswick, Maine, where John Henry taught classics at Bowdoin College. They then moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, where John Henry took up his position as Professor of Classics.

In 1887, when Frances was two years old, illness forced John Henry to resign his professorship and the family moved to Newbury. Johnson relatives pooled their energies and resources to help the family after John Henry’s death, Louise and Frances remained in Newbury until Louise’s marriage to Albert Pillsbury in 1889. The family then moved to Boston where Pillsbury, a prominent lawyer and up-and-coming politician, was building a house for his new family at 583 Beacon Street.

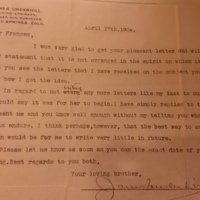

Although Frances was very young when her father died, John Henry Wheeler bequeathed to his young daughter an inquisitive mind, love of learning, and enjoyment of riding fine horses. Frances learned more about her father in 1895, when her mother took her on a yearlong tour of Europe. A visit to Bonn allowed Keyes to meet her father’s former colleagues. Letters written during this visit by Louise to John Henry’s family allowed Keyes to later recount how they praised her father’s scholarship. [3] Her introduction to her father’s European intellectual world and her visits with her brother James, Jr., who had graduated from Harvard and was studying in Geneva, were highlights of the European trip for Frances. For Louise, the trip was a respite from the tensions that had surfaced in her relationship with Albert. Their marriage did not survive their separation and, in 1897, the couple was divorced.

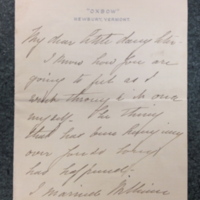

After returning from Europe, Louise and Frances moved back to Newbury while James moved to Colorado, where he began his career as a geological engineer. The European travels of 1895 and 1896 are documented in correspondence between Louise and the Wheeler family in Woburn, Massachusetts, including Louise’s letters to her sister-in-law, Cornelia (Fannie) Hill.

In her memoirs, Keyes makes clear that she believed her mother’s social striving, her flirtatious behavior with men, and her multiple (and ultimately unlucky) marriages exacerbated the feelings that she had expressed in 1918 about coming from a mixed heritage and environment. None of that is evident in the Atlantic Monthly article but it might have been in her consciousness because just three years earlier her mother Louise, then sixty-seven-years old, had married a twenty-two-year-old Newbury dairy farmer named William Taisey.

The complexity of Keyes’s relationship with her mother Louise, as Keyes tells it in her memoirs, makes for unsettling reading. The family correspondence matches up with this daughter’s pained portrait of a mother whose expectations for her children were often different from the intellectual aspirations and personal desires they had for themselves. The correspondence also reveals how they maintained bonds across time and space.

1) FPK, “How I Learned to Write,” Good Housekeeping, October 1924, 24. ↵

2) “Frances Parkinson,” Granite Monthly, 3rd Quarterly Issue, 1918, 7.↵

3) Roses, 112. The colleagues are Franz Bücheler and Hermann Usener.↵

Related Documents: