Becoming Frances : Education

Frances Parkinson Keyes wrote in her 1960 memoir that her year in Europe was “the most valuable one of my entire education” but she also made clear that her greatest educational debt was to the encouragement she received at an early age from her Grandmother Wheeler. [1]

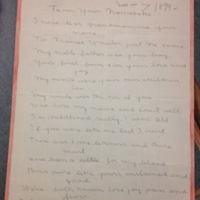

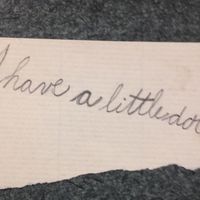

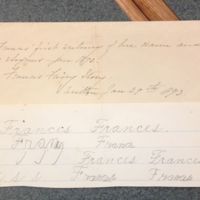

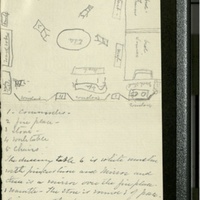

Grandmother Wheeler taught young Frances how to read, initiated her studies in foreign languages, tackled Frances’s dreaded subject of mathematics, and set an example with her hard work and frugal ways. Frances’s love of her grandmother is evident in her descriptions in Roses in December and in their correspondence. In 1899, fourteen-year-old Frances wrote a poem for her eighty-year-old grandmother, “From Your Namesake.” Just seven years earlier, Frances was practicing her penmanship by writing her name and letters in the ways taught to her by her grandmother. Before that, at age four, her grandmother taught her to read from Bible and years later Frances used the same method to teach her young boys to read. [2]

Frances’s formal education began in Boston at Miss Bertha Carroll’s Day School. She was then educated at a Swiss boarding school during her 1895 European trip with her mother. When they returned home, her education came from a new governess, Mademoiselle Riensberg, who Louise had hired to facilitate Frances’s language studies in French and German until Frances left for Boston to attend Miss Winsor’s School.

Later in her life, Keyes remembered that she was not a “naturally brilliant student” but she considered herself “conscientious and hardworking, with a good memory and a certain facility for learning languages” and writing.” But her “good marks were the result of unremitting labor,” she concluded. [3] Frances wrote her mother about how she labored over her books. “I was disappointed with the ‘very good’ in Latin, but otherwise satisfied,” she wrote on February 6, 1901. At the end of the month, on February 27, she told her mother “I am doing perfectly wretchedly at school and am about wild over it; I only got a B+ on my Algebra exam.” When she did well, she was ecstatic. “I got an A on a theme on Friday though Miss Kinsman declared she wouldn’t give an A,” she wrote on January 13 of the same year. “It is to be sent to Miss Winsor.”

The mission of Miss Winsor’s was to prepare “women to be self-supporting” and the opening of women’s colleges during this era encouraged more women to think about continuing their education. Frances attempted to enter Bryn Mawr College but a combination of back troubles and headaches brought on by dental problems, and an inability to handle the stress of her studies, resulted in less than perfect exam scores. The health problems that Frances first displayed during her school years continued throughout her life and she was often suffered from debilitating physical problems.

While Frances’s teachers encouraged her to continue her studies and retake her exams, her mother urged rest, which meant a return to Newbury. The letters Keyes wrote to her mother during this time period detail her agonizing efforts to maintain a healthy state of body and mind, but they also contain delightful stories about her visits with friends and relatives. During times of unhappiness with her mother, Frances was sustained by her many friends, including Mary Tudor [Gray] and Elizabeth Sweetser. Mary did more for her “materially and psychologically” than any other woman, Keyes wrote in her memoir, and Elizabeth “meant more to me throughout my teens than almost anyone else in the world.” Her love for Elizabeth “had no relation to the ordinary schoolgirl crush,” Keyes stated; “her confidence in my character and capabilities was the foundation for much that I have been and done in the entire course of my life.” [4]

Notes:

1) Roses, 101. ↵

2) Roses, 42-43. ↵

3) Roses, 237. ↵

4) Roses, 43, 76, 80, 162; All Flags Flying, 3, 125, 143. ↵

Related Documents: