Restless : Liveright

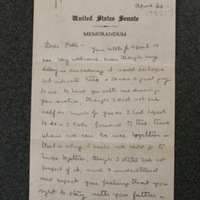

The last of Frances Parkinson Keyes’s 1932 travel articles, “Irack [sic], The Land Amid the Rivers,” appeared in July. In this same period, Keyes began working on the manuscript for a new book at the behest of her publisher, Liveright Inc., which had already published her novels Queen Anne’s Lace and Lady Blanche Farm. This novel, Senator Marlowe’s Daughter helped establish Keyes as a bestselling novelist of international renown, but not before it was drawn into a crisis that threatened her business relationships and which altered the trajectory of her writing career

In June 1928, Keyes entered into a contract with Horace Liveright Inc., agreeing to option the company the rights to her next two books. Keyes later commented that the terms of the agreement were “not only just but generous.” Although 1928 had been a year of record sales for the business and its eponymous publisher, Horace Liveright, success was short lived. The stock market crash in late 1929 devastated Liveright, whose reputation for generosity to his authors and lavish spending strained company resources. [1] Though the business would endure after distancing itself from its controversial president, by spring 1933 Liveright Inc. was near bankruptcy.

The timing could not have been more inopportune for Keyes. In January 1933 she had signed a contract offering Liveright the rights to Senator Marlowe’s Daughter and at the end of March she submitted her completed manuscript to Julian Messner, a vice president of the publishing house who had become a close personal friend as they worked together editing her manuscripts. Not one month later, Keyes was informed by a rival publisher of “conflicting rumors” on the solvency of Liveright Inc. and the status of her manuscript. Although royalties for works published by Liveright had not been paid in over a year, Keyes looked the other way because of the support and partnership she received from the firm in general, and from Julian Messner in particular. Worse still, no advance had been paid to Keyes upon the signing of the contract for her new work but instead was to be remitted to her at the time of publication. Keyes had made a serious business misstep, one she had vowed never to do again after her wretched experience with Houghton Mifflin over the publication of Lady Blanche Farm. Since the manuscript was no longer in her possession, and with the possibility that creditors would make away with her novel without compensation, Keyes faced the prospect that her work of more than six months was lost.

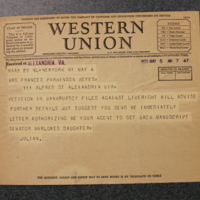

In the wake of this professional crisis, Keyes was also challenged by financial and personal difficulties in her private life. In November 1932, a fire ravaged the home in Alexandria, Virginia leased to the Keyes family. [2] The damage was estimated at $5,000 but, as of the following February, the Keyes family had not yet received payment from their insurance company. At the same time, twenty-six-year-old John Keyes, Frances’s middle child, was unemployed and living with his parents after failed attempts to enter the U.S. Foreign Service. Keyes was sensitive to her son’s lack of opportunity during the Depression and later remarked that, “if ever a boy had a secession of blows in trying to establish himself in a career, [John] has.” (John Keyes even tried his hand, unsuccessfully, at “tramping the streets” as a door-to-door salesman.) Keyes was also largely responsible for providing her youngest son Peter with a monthly allowance while he studied at Harvard, and subsidizing her eldest, Henry, as he worked towards becoming an attorney. In addition, Keyes maintained household and secretarial help. When John Keyes remarked in a letter to his brother in early 1933 that family funds were at “the usual low ebb,” he recommended letting go of one of their employees, for in doing so the family would have “sufficient income to manage the necessary things quite easily.” John’s understanding of what was “necessary” likely failed to take into full consideration the expenses that allowed Frances Parkinson Keyes the ability to pursue her career and to support her family in a manner of her choosing.

Under such circumstances the loss of Senator Marlowe’s Daughter wouldhave been a disastrous setback for Keyes. Fortunately, with the help of Julian Messner, the manuscript was restored to her possession. With several publishers now courting Keyes for themselves, her prospects improved significantly. Yet Liveright’s bankruptcy caused great and lasting distress for Keyes, who continued to confront financial difficulties as she established her career as a novelist. Keyes would later write, “I would rather never have another book published as long as I live than ever go through such an experience again.”

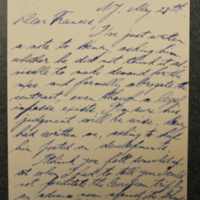

As Keyes weighed her options in selecting a publisher, she remained faithful to the business relationship she had established with Julian Messner. After the announcement of Liveright’s bankruptcy, Keyes wrote to her son Peter that Messner “has been very good to me, and I cannot abandon him so long as there is the possibility that he will go on publishing books; either with Liveright or with some other firm.” This loyalty reveals much about the character of Frances Parkinson Keyes, and about her commitment to reciprocity that advantaged both parties in an exchange.

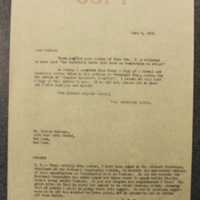

Whether the exchange was of material or of ideas, Keyes understood the value of original work. At the same time, she was aware that her own choices had an impact on others, and she was careful to consider their needs when making her decisions. In a July 1933 letter to Messner, Keyes reflected that, “I have tried to consider my publishing problems as conscientiously and comprehensively as possible and without losing sight of the fact that these affect not only you and me, but also the small number of persons who are very dear to me and for whose welfare I am in large part responsible.” Here, Keyes was careful to acknowledge the important work of her secretary, Harriet Whitford, who was a steadfast supporter even though she had recently been “over-worked and under-paid.” When Keyes finally committed to work with Julian Messner as the primary publisher of her novels, she established a professional alliance that would last for more than two decades.

Notes:

1) Thomas Dardis, Firebrand: The Live of Horace Liveright (New York: Random House, 1995), xvi.↵

2) “Home in Alexandria Damaged by Blaze,” Washington Post, November 28, 1932. ↵

Related Documents