Restless : Germany

Not all of Keyes relationships in this period reflected mutual support and self-sacrifice. Writing to her son Peter in March 1933, Keyes remarked on her husband Harry’s recent withdrawal from the marriage: “Daddy maintains his gloomy attitude of complete retreat, which is unpleasant to live with and very bad for the furtherance of my new projects—However, as nothing will move him from his selfish seclusion, I am doing the best I can without him.” The pursuit of personal aims in the face of resistance from those closest to her mirrors Keyes’s earlier narrative on the genesis of her career as a writer when “nobody believed that she could write and nobody wanted her to write.” [1]

In her April 1933 Good Housekeeping article, Keyes wrote that “the woman who has learned to make a good companion of herself by widening the scope and variety of both her mental and physical activities will never be unhappy or restless because she has temporarily been left without any other companionship.” The article, framed as a letter from Keyes to an “old fashioned housewife,” occasionally reads as though it is self-addressed, albeit indirectly. Keyes did not reflect the article’s intended audience, who she describes as a “woman whose freedom from financial responsibility and anxiety is guaranteed by the man whom she has entrusted her destiny” and who “has certain undeniable advantages over the woman who is perpetually harassed by the consciousness that she must not only be self-supporting, but that she also must contribute to the support of others.” Instead, Keyes, by virtue of her many obligations and with the absence of support she received from her husband, appears more closely aligned with the latter figure she describes.

Keyes’s own restlessness was again roused in early 1933 when she expressed the desire take a summer trip to Europe to research The Great Tradition, a sequel to Senator Marlowe’s Daughter. Keyes was attracted to the possibility of visiting Germany in particular, an objective that became more critical in June when she was asked to present the prestigious annual mid-winter address of the National Geographic Society.

Despite not having the means to travel to Germany and recognizing that her professional contacts were not in the position to provide her funding, Keyes remained hopeful that she could make the trip. She wrote, “sometimes the way opens when everything seems obstructed, perhaps it will turn out that way with Europe.” Keyes considered many options to facilitate her trip, including traveling with companions who would defray costs. Having secured the interest of family friends, Dr. and Mrs. Titus, who wished Keyes to chaperone their daughter Ruth on her voyage to Germany, Keyes remarked, “If I could take her and another passenger who would pay her own expenses, of course my problem with how to make the trip would be less complicated as far as the financial aspects.” Keyes’s optimism was rewarded and in October 1933 she sailed for Germany. It is unclear, however, who arranged and paid for her trip.

During her travels through Berlin, Keyes came into contact with the Carl Schurz Vereinigung (Carl Schurz Society). Founded in 1926 to further German-American friendship, the group maintained a palatial house in the Tiergarten district of the German capital where important American tourists were received and provided with various forms of travel assistance. [2] Bettering relations between Germany and the United States was a cause that Keyes had herself taken up when she wrote about her 1931 trip to Germany in Good Housekeeping. Keyes was pragmatic in presenting her impressions of the country. She wrote that she would leave the task of contextualizing the social, political, and economic “chaos” of Weimar Germany to experts in order to focus on her own personal experiences of the German nation and people. In adopting this approach, Keyes hoped to provide her audience with “a better comprehension of a place and a people from whom we have become estranged and concerning whom we lack both sympathetic and intelligent information.”

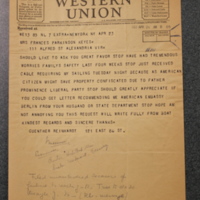

When Keyes returned Germany in the fall of 1933, much had changed since her last visit. Germany was no longer a parliamentary democracy. The National Socialist Party had made great political gains in the elections of November 1932 and, following Adolf Hitler’s appointment to Reichskanzler (Reich Chancellor) on January 30 and the Enabling Act of March 5, 1933, persecutory measures against marginalized groups, including Jews and political opponents, were quickly introduced. We do not know how Keyes’s understanding of sympathetic information evolved after she encountered the socio-political environment of Nazi Germany. Yet Keyes had become aware of persecutory measures of the Nazi regime even prior to her journey. In April, Keyes received an urgent telegram from Günther Reinhardt; “WOULD LIKE TO ASK YOU A GREAT FAVOR—HAVE HAD TREMENDOUS WORRIES OF FAMILY’S SAFETY,” the telegram read. Reinhardt, a New-York based publishing contact, was a German-Jewish émigré whose prominent and accomplished family in Germany were dismissed of their positions and their assets frozen following the introduction of the discriminatory April Laws. Although they were only acquaintances, Reinhardt hoped that Keyes, the wife of an American Senator, might have pull with American officials who could assist his loved ones who were among the early victims of Nazi persecution.

The persecutory legislation introduced by Hitler in April 1933 was also adopted by the Carl Schurz Society, which imposed Gleichschaltung (“Coordination”) of its membership by ousting those deemed “politically, and racially unreliable.”[3] This move followed earlier efforts to ensure the group’s financial solvency by becoming increasingly aligned with nationalist, and National Socialist, interests. By the time of Keyes’s visit, the group had become closely affiliated with the Propaganda Ministry, hosting speeches by Josef Goebbels in which he promoted a “new era of mutual understanding,” and rallied against “atrocity stories” circulating in the foreign press. [4]

While visiting Germany in 1933, Keyes appears to have avoided behavior that might have been perceived as an endorsement of the new regime. After false reports were circulated in the Washington press that Keyes was to interview Adolf Hitler, she contacted E. de Haas of the Carl Schurz Society to subtly address the “confusion,” which had prompted a response from the American Consul in Hamburg. At the same time, Keyes did not speak publicly of objections to what she experienced of Nazism. When Keyes finally spoke before her audience at Constitution Hall on behalf of the National Geographic Society in January 1934, she praised Germany as a “greater country,” a country more unified, revitalized, and where “one feels that they are on the way to a period of growth and revival.” Moreover, Keyes expressed the hope that “her lecture would promote better understanding between the American and German people.” [5] This refrain echoed objectives of the Carl Schurz Society and suggests that Keyes’s speech may have been influenced, to a degree, by her contact with the group. One might speculate that Keyes remained publically impartial in order to maintain the relationships with the organizations and individuals that had supported her German travels and provided for continued access to the country. There is little indication as to what information Keyes communicated with her friends and colleagues upon return from Germany but she personally shared her observations with prominent political figures, including President Franklin Roosevelt. Whether her private conversations reflected the tone of her public speeches remains unclear.

Keyes made two additional trips to Germany after her 1933 visit. In 1937, Keyes was called to generate a report on German housing conditions at the behest of the Federal Housing Administration. However, this was not her sole aim in traveling to Germany. Keyes suggests additional purposes in correspondence with then German Ambassador to the United States, Dr. Hans Dieckoff. While seeking a visa for her “special passport,” Keyes casually remarked to the Ambassador that, “incidentally, I am going to do more work on a novel that I am presently engaged in writing—some of the scenes are set in Germany.” By this time, Keyes had been involved in the planning, research, and writing of The Great Tradition for more than four years. This prolonged duration is exceptional given Keyes’s remarkable productivity in the period. In the five years following the 1933 release of Senator Marlowe’s Daughter, Keyes had published seven books.

The trip was more productive than she imagined and she arrived home with “40,000 words” and “a wealth of colorful impressions” from her visits to Poland, France, and Germany. According to Hope Ridings Miller, writing in the Washington Post,” the “trip included much more than a novelist’s search for background and inspiration.” It provided her with the opportunity to visit “Nuremberg during the Nazi party rally” and she “had a ring-side seat at the most exciting event in recent times.” [6] Not revealed in Miller’s account was that the Carl Schurz Society had arranged for Keyes’s attendance at the 10th Nazi Party Congress that took place in Nuremberg from September 5-12, 1938. Although the event was a first for Keyes, the 10th Party Congress would be the last Nuremberg Rally. An eleventh rally would be cancelled as a consequence of Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 and the subsequent declarations of war on Germany by Great Britain and France, both allies of Poland.

After attending the Nuremburg rally, visiting other Germany cities, and spending time in Poland, Keyes went to Lisieux, France to conduct research for her book on Saint Bernadette of Lourdes. When she arrived in Lisieux, “war fears had subsided,” Miller wrote,” but in fact, Keyes was “caught up,” to use her own phrase, in the early phases of the Second World War and, upon arriving home, finished the novel that she had been working on for so long. In November 1939, The Great Tradition was finally released. The reviewer for the Washington Post called it “the best fiction yet to come from Mrs. Keyes’s prolific pen.” [7]

The Great Tradition presents the trials of a young German-American man who returns to the “Fatherland” in the early 1920s. In her narrative, Keyes addresses the rise of Nazism in Germany and its appeal to directionless young men. For the protagonist, Hans Christian, National Socialism is a corrupting force that “robs him of his heritage,” and “embitters his trusting, too innocent soul.” [8] The book contains many passages that reject Nazism and its influence on German society. Perhaps, in writing of the destructive influence of Nazism in her fictive writing, Keyes remained true to what one German observer had praised about her work; she, as a writer, could “do more in a book to give [Americans] a picture of Germany than many politicians and lecturers are able to do.” While we have little indication of how closely the picture Keyes crafted of Germany in the late 1930s reflected her own opinions of Nazism, it does suggest a marked departure from the tenor of her public speeches earlier in the decade.

Notes:

1) Maud McDougall, “Woman Who Couldn’t Hide Under A Basket,” Oregonian, August 29, 1920. ↵

2) C. E. Carpenter, “A Delawarean in Naziland,” Delmarva Star, February 17, 1935; Rennie Brantz, “German-American Friendship: The Carl Schurz Vereinigung, 1926-1946,” International History Review 11:2 (May 1989): 229-251. ↵

3) Brantz, “German American Friendship,” 241-242.) ↵

4) “Goebbels Asks Nazi Support From America,” New York Times, October 9, 1933. ↵

5) Washington Post, January 26, 27, 1934. ↵

6) Hope Ridings Miller, “Frances Parkinson Keyes Returns from Europe,” Washington Post, October 20, 1938. ↵

7) Hope Ridings Miller, “A Germanic Galahad,” Washington Post, November 12, 1939. ↵

8) “New Novels,” The Age, January 12, 1940. ↵

Related Documents