A Lady of Letters : Keyes' Home at Good Housekeeping

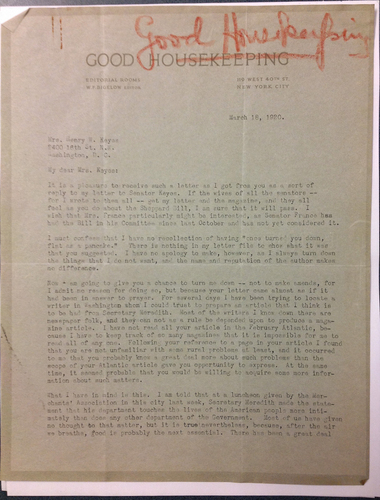

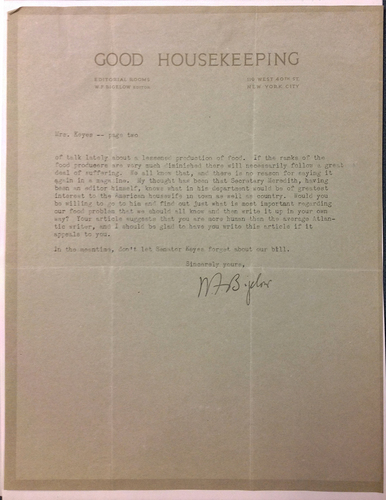

One of the more interesting things to understand about Keyes as a magazine writer has less to do with the actual content she was created and more to do with her relationship with those who ran the magazines. Throughout Keyes two decades of employment at numerous magazines, she maintained a frequent and vast correspondence with her editors and publishers. Keyes’ most extensive work-related correspondence was with W.F. Bigelow, the editor of Good Housekeeping. The numerous letters Keyes and Bigelow exchanged reveal a great deal of information about Keyes’ life, her political interests, and her influence in the publishing world.

Under Bigelow’s editorship, Good Housekeeping was an activist organ working on behalf of what was known as the “women’s agenda” of the post-suffrage era. One of its primary causes was the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act and Keyes wrote often about the lobbying effort to pass this maternity and infant health care legislation. Bigelow, Keyes, and other contributors to Good Housekeeping were also advocates for child labor legislation, opposed the introduction of an equal rights amendment to the U.S. constitution, and took a stand other political measures of interest to progressive women.[1] This political emphasis of the magazine may have been one of the reasons that Keyes considered the magazine her journalistic home in the early 1920s.[2]

In one of his earliest letters to Keyes, Bigelow reveals with his numerous compliments and comments Keyes’ prowess as a writer and her social and political prominence. Addressing an article that Keyes had published in the Atlantic Monthly, Bigelow states that Keyes is “not unfamiliar with some rural problems … [and is] probably … [aware of] a great deal more about such problems than the scope of the Atlantic article gave [her an] … opportunity to express.”[3] After only two years as a magazine writer, Keyes had become a major figure in the literary world, in part because of her status as a Governor’s wife but also because of her unique voice and personality. It is clear from her writing that Keyes had a strong sense of direction and ambition. She had a definite idea of the sort of writer she wanted to become through her work for Good Housekeeping; she wanted to be, she told a reporter, “a lady of letters.” Although she is best remembered as a popular novelist it is important to remember that she valued her magazine articles, especially the ones she wrote on serious political subjects in the 1920s.

Keyes did not only want to become “a lady of letters.” She also wanted to help other women in the literary field and she dedicated her energies to mentoring them. For example, while writing about the Sheppard-Towner Act for Good Housekeeping, she met Emily Newell Blair, who was a founder of the National League of Women Voters and the Woman’s National Democratic Club. Despite their partisan differences (Keyes was a Republican), Keyes wrote on Blair’s behalf when Blair sought a position as an editor at Good Housekeeping.[4]

[1] Frances Parkinson Keyes, “Letters from a Senator’s Wife,” Good Housekeeping, March 1921, 12-13, 100-105 and July 1921, 35-36; 136-139; Keyes, “The Equal Rights Bill,” Good Housekeeping, February 1923, 28-29; 180-185.

[2] Jennifer Burek Pierce, “Science, Advocacy, and ‘The Sacred and Intimate Things of Life’: Representing Motherhood as a Progressive Era Cause in Women’s Magazines,” American Periodicals 18, no. 1 (2008): 69-95.

[3] Letter from Bigelow, March 18, 1920.

[4] Frances Parkinson Keyes to Emily Newell Blair, 25 January 1925, Box 1, Folder 1 Frances Parkinson Keyes Papers, Special Collections, University of Vermont. The correspondence between Blair and Keyes continued through the 1930s and demonstrates Keyes’s commitment to helping women obtain professional positions. For another example of this type of mentorship and support see the correspondence between Keyes and Eleanor Carroll, Box 1, Folder 3, Keyes Papers, UVM.