Capitol Kaleidoscope : Publishing

Frances Parkinson Keyes wrote her “Letters from a Senator’s Wife” column for Good Housekeeping from March 1921 until March 1937. According to one account, the column helped increase the magazine’s circulation by about 100,000 readers. [1] Her columns of the early 1920s described the social-political life in Washington and bills before Congress. They celebrated women’s individual and collective achievements and brought attention to ongoing efforts for a child labor amendment (which Keyes supported) and the equal rights amendment (which she opposed). She reported on the Conference on Limitation of Armaments, the Pan-American Conference of Women, and the meetings of the Cause and Cure of War. She discussed marriage, motherhood, and her own and other women’s illnesses.

In June 1923, Keyes announced to Good Housekeeping’s readers that she would be traveling to Rome for the Congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance and in August readers were able to read not only about the conference but also about her interviews with Benito and Rachele Mussolini. Benito Mussolini, who became Italy’s Fascist leader the previous November, was reluctant to grant interviews to foreign correspondents but, through her political connections, Keyes was able to gain access to the dictator and she wrote positively about his leadership and his family. The interviews were, she later wrote, her “first scoop” and when she returned home she took another step forward in her career when Bigelow appointed her as one of Good Housekeeping’s associate editors.[2]

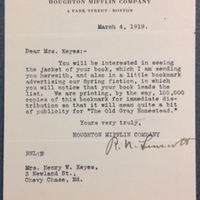

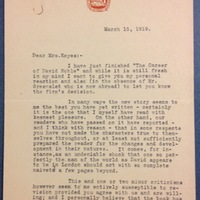

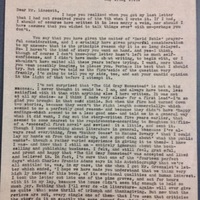

Keyes’s success with Good Housekeeping was balanced by the difficulties she was having with Houghton Mifflin in getting her novels published. Two months after the publication of The Old Gray Homestead, Keyes sent Houghton Mifflin the manuscript for The Career of David Noble. After reading it, editor R. N. Linscott informed Keyes that the press had decided that the book was not what they hoped for. Still, they told her, they wanted to hold onto the manuscript and would talk with her “about it again later on.” Her Boston editor reported that it had “put it in his safe for the present.” [3]

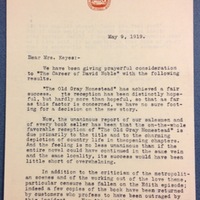

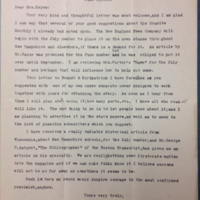

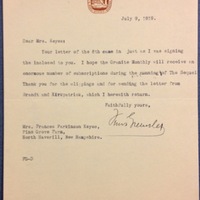

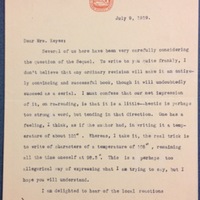

There is enormous demand for the “quiet happy story of country life,” Linscott wrote Keyes on May 9, 1919, and he suggested that, since she had made her start as an author of farm life, she should continue in that tradition. Keyes did as Linscott suggested and over the summer at Pine Grove Farm she worked on the manuscript called Lady Blanche Farm. She also made one additional attempt to get Houghton Mifflin to publish an already completed manuscript called The Sequel. In July 1919, when editor Ferris Greenslet informed her of the press’s rejection, Keyes was able to respond immediately with the news that it would be published as a serial in Granite Monthly.

After two months of hard writing at the farm, Keyes finished Lady Blanche Farm, sent it to Houghton Mifflin, and in late October received the news that they were not only rejecting this new story but were sending back the manuscript of The Career of David Noble. Greenslet wrote Keyes on October 27 that the story did not have the “‘big punch necessary for a wide sale.” Linscott tried to soften the blow a few days later by telling Keyes that she was “particularly successful” with her local color and Yankee humor and that he hoped someday to reread the story in book form. He had the chance. F. A. Stokes published The Career of David Noble in August 1921.

Linscott’s diplomatic letter was offset by the fact that inserted into the returned manuscript of The Career of David Noble was a memorandum from Linscott to B. H. Ticknor of the Riverside Press. The memorandum called the manuscript a “little too crude and immature” for publication but “if we turn it down we probably will not get a chance at another of her” stories. When Keyes returned the note to the publisher, she received “not an apology,” which led her to conclude that publishers “are not governed by the same rules that apply even in politics.” She believed she had learned a valuable lesson and she vowed that she would “never undertake any writing for a publisher which involved time and effort unless the verbal request that I should do so was reinforced with a written one and at least a token payment of hard cash.” [4]

The Old Gray Homestead sold 5,000 copies in its first year of publication and the money Keyes earned paid for doctors’ bills, private school tuition, and the duties that went with being a Senator’s wife. In the fall of 1921, a newspaper article reported that “Earnings of Senator Keyes’ Wife, Noted Author, Exceed Her Husband’s In Washington.” [5] Whether this was true or not, it was not the kind of publicity that Keyes needed or probably wanted. In All Flags Flying, she relates that during this time Harry told her that “it would be more helpful” if she “were strong enough to do the washing and save money that way, instead of trying to earn it by writing.” She was “deeply hurt” but tried to be understanding. Harry missed New Hampshire and the farm; he was not happy in Washington, where sports were played for money and politics seemed too progressive. More and more, Frances and Harry went their separate ways. [6]

In July 1923, another newspaper report floated the idea that Frances might succeed Harry in the upcoming election. Frances was identified as a “New Hampshire Woman Known as Writer of Observations on National Politics” and a picture of her with her three sons ran under the headline. The report acknowledged that Harry had “definitely announced his purpose of running for reelection in 1924” and that he “denied published reports” that Frances “would be a candidate in his stead.” Frances, the report also stated, was “at present in Paris, en route to Holland, where she will be presented to the royalty of that Nation.” [7]

Notes:

1) Robert Wernick, “Queens of Fiction, Life, April 6, 1959, 139-152. ↵

2) All Flags Flying, 229. ↵

3) All Flags Flying, 137.) ↵

4) All Flags Flying, 141.↵

5) Bisbee (Arizona) Daily Review, October 1, 1921. ↵

6) All Flags Flying, 135-136. ↵

7) Boston Daily Globe, July 10, 1923; New York Times, July 10, 1923. ↵

Related Documents