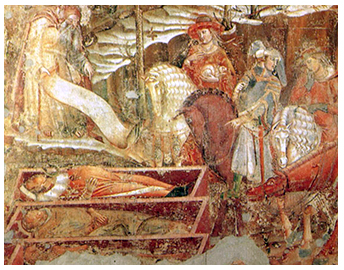

Italy in Crisis: Plague in the 14th Century

Description

..."What more can be said except that the cruelty of heaven (and perhaps in part of humankind as well) was such that between March and July, thanks to the force of the plague and the fear that led the healthy to abandon the sick, more than one hundred thousand people died within the walls of Florence. Before the deaths began, who would have imagined the city even held so many people? Oh, how many great palazzi, how many lovely houses, how many noble dwellings once full of families, of lords and ladies, were emptied down to the lowest servant? Oh, how many memorable pedigrees, ample estates and renowned fortunes were left without a worthy heir? How many valiant men, lovely ladies and handsome youths whom even Galen, Hippocrates and Aesculapius would have judged to be in perfect health, dined with their family, companions and friends in the morning and then in the evening with their ancestors in the other world?"

..."What more can be said except that the cruelty of heaven (and perhaps in part of humankind as well) was such that between March and July, thanks to the force of the plague and the fear that led the healthy to abandon the sick, more than one hundred thousand people died within the walls of Florence. Before the deaths began, who would have imagined the city even held so many people? Oh, how many great palazzi, how many lovely houses, how many noble dwellings once full of families, of lords and ladies, were emptied down to the lowest servant? Oh, how many memorable pedigrees, ample estates and renowned fortunes were left without a worthy heir? How many valiant men, lovely ladies and handsome youths whom even Galen, Hippocrates and Aesculapius would have judged to be in perfect health, dined with their family, companions and friends in the morning and then in the evening with their ancestors in the other world?"

--Boccaccio, The Decameron

Boccaccio described the dramatic toll of the most perilous plague epidemic in history, the 1348 wave of the Black Death. In less than a year, the plague devastated an Italy already in political and social turmoil. The "Little Ice Age" had begun by the start of the century and had caused the soil quality to decline. As a result, the Great Famine began in 1315 and had claimed many lives and caused mass malnutrition that weakened the defenses of survivors during its two-year duration. Religious crises abounded as well. The Babylonian Captivity (when the papacy moved to Avignon, France) and the Great Schism (a period during the 14th century when three popes claimed the seat of Peter) brought confusion and a dearth of authority. By the third quarter of the century, wars were waged against the Papacy. In addition to all of this, in several cities, the masses of manual laborers rose up against the domination of the rich elite, wreaking total social upheaval. As these crises mounted, the people began searching for answers and they blamed the stars, poor religious leadership and widespread sin for their downfall.

Just as Virgil had cautioned Dante as he entered into Hell in the Divine Comedy, "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here," hope was, understandably, being abandoned. As the plague spread like wildfire, claiming the lives, in some cities, of more than half of the population, many suspicions and superstitions came to the surface as people struggled to find its causes. Jews, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims, and people with skin conditions were targeted and killed because they were considered carriers of disease.

The devastation of the plague naturally had an enormous impact on the society of survivors left behind as the plague dissipated, at least temporarily, by 1350. As rebuilding began, looming doubts, a growing concept of the individual, the lingering questioning of authority, religion and social structure a desire for the "good old days" of the great Roman Empire, along with increasing economic prosperity by the end of the century, served as catalysts for a new age, the golden age of the Renaissance, which, by the end of the century, was already beginning to bloom.

Credits

Exhibit created by the students of ART155: Plague, Art & Crisis 1300-1400, University of Vermont.